When Oliver Hardy would turn to Stan Laurel, square his jaw and then give his tie a little twirl, you always knew what was coming. “Well, here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into.”

Exactly.

Our friend, Brenda, thought anything she could do, Jill and I could, too. This was almost always not true. Brenda had made JV cheerleading, and she was sure we could all make Varsity together. Her overflowing confidence sometimes coursed in my direction, and I would temporarily lose my mind.

That’s how I ended up at Varsity tryouts. Cue Oliver Hardy.

We broke into small groups with an actual cheerleader directing us. I had expected a few hours of explanation, maybe a film about cheer leading, or some diagrams I could study before I actually had to do anything. She spent a minute introducing herself. (As if we didn’t know her name. She was a cheerleader!)

And then without warning she said, “Okay! Now line up and let me see your split jumps, one at a time.”

With nothing available to stave off the impending humiliation, I jumped.

She said, “Okay! Now you’ve just got to work on getting it in the air.” Her turn of phrase made me question if my feet had ever left the ground.

Jill and I didn’t go back for the second day of tryouts. We tried out for Chiefettes instead, a kick line that performed during halftime at football games. Chiefettes got to link arms with each other and keep one foot on the ground at all times, which worked out better for us.

Brenda continued to conquer new frontiers. For one thing, she had boyfriends. Jill and I had dates — the sweet, unsullied kind where you went to the movies and then you ate French fries at the diner — the kind of dates our mothers went on.

One night after one of these, annoyed at the persistence of a boy I didn’t like all that well, I got to use the line, “I’m not that kind of girl!” I threw it out there indignantly, the way I’d heard it delivered on television.

The boy (embarrassed, I know now) walked me home in silence. As I was putting my key in the front door, he yelled out his parting shot from the sidewalk. “Oh yeah? Well, guess what? You’re a cold fish!”

Was I a cold fish? It was impossible to know where I was on the sexual continuum when I hadn’t yet had any experience of any kind. I’d read about “How to Fine Tune Your Relationship” in magazines like Glamour and Seventeen, but those articles were deliberately vague and sometimes alarming. I was petrified of being frigid, something that got a lot of ink. But — from all I’d picked up — it only afflicted married women so I figured I was off the hook.

In every picture I have of high school graduation, the three of us and our parents are all squinting into the sun. Brenda won awards, engraved charms she would put on a bracelet. I graduated #304 in our class of 616, my goal of slouching toward middle-of-the-road now complete. Our cakes had butter-cream icing. Our parents gave us the portable typewriters we would take to college.

And then, two weeks later, our phone rang very late and woke me up. I heard my mother answer it and say, “Oh, dear! Oh no!” Then I heard her coming up the stairs to my room.

“Brenda’s mother is on the phone,” she said. Do you know where she is?”

I didn’t.

“They just found a note that says she’s gone away with that guy. To get married!”

That Guy was the name we had taken to calling Brenda’s latest boyfriend. We didn’t think he was going to be around long enough to bother with his real name.

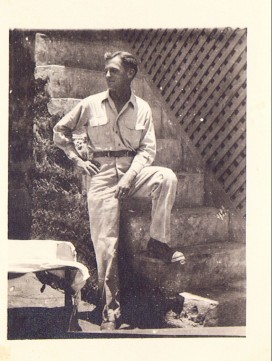

That Guy was someone Brenda’s brother had brought home on leave from the army. Her family had been letting him sleep in their family room until he had to get back to his base and then leave for his second tour in Vietnam. It was supposed to be a week, but now it had been a month and he was still hanging around, lounging on the couch with his guitar all day.

We could see that Brenda was crazy about him, but we didn’t get it. He hadn’t gone to college. He was divorced. He was old (26). Three strikes. And his guitar playing was pretty weak.

Brenda had eloped, just like in the movies but without the whooping and happiness and the old jalopy sailing down the road, with the words The End superimposed on the screen. Two days later, the new Mr. and Mrs. That Guy got up their nerve and resurfaced back in Massapequa, to retrieve her clothes and be on their way to his base in Texas.

Jill and I were invited over to say goodbye. We walked in the front door just as Brenda’s father was begging them to get an annulment. But Brenda was 18 and there was nothing they could do about it. And she was in love, she told them. After the first wave of hysterics subsided, Brenda went into spin mode.

“We’ll have a church wedding as soon as he gets back from Vietnam,” she said. “Tell Father O’Connor we’ll be in touch.”

Brenda had mastered this skill in junior high school. She changed the topic just slightly, adding charming little details to warm up her mother, who was alternately weepy and angry.

“Oh Mom, the Justice of the Peace was so sweet. He sat with us afterwards and told us that he and his wife have been married for 55 years.”

Brenda’s mom said, “Did you at least have flowers?”

“Yes! Of course I did!”

* * *

So that fall, instead of her first-choice university, where she already had a room, a roommate, and a challenging freshman schedule waiting, Brenda and her husband drove to Fort Hood, Texas.

Jill and I, now freshmen in college, gave Brenda’s letters a big dose of parsing. I guess we’d spent all those years discussing the ins and outs of what married life would feel like, she figured she’d make good on the investment.

Their apartment on base: “Luckily it’s furnished, and it’s mostly Danish Modern!” Her dinner menus: “One thing I’ve learned cooking for a soldier. Buy plenty of meat!” The part we were most interested in: “I can’t tell you how much I love my late nights and early mornings with my husband.”

We analyzed every line. And we had so many questions we didn’t ask. Did she wear her hair rollers to bed? Did she close the bathroom door? Did they have sex with the lights on? Did she let him see her without makeup? Or did she wake up an hour before he did and put mascara and lipstick on in the dark? (I’d read “Tips to Keep Your Man,” recently and thought it resonated.)

As intrigued as we were by Brenda’s letters, Jill and I just dug in deeper to the way we’d always been. Our goals hadn’t changed much since 8th grade. Pristine, virginal weddings (in June, of course). A college degree. A teaching job. And a house where we’d sew gingham curtains and never think of cooking a meal unless it came straight out of our Betty Crocker cookbooks.

Apparently the news that we were coming of age in the late 1960s had been kept from us until this point.

But not for long.

[Up on Monday: A Reunion When I Least Expected It]