My list of college accomplishments was short. I was guilty of falling in and out of love hard and spending too much time in front of my mirror. I didn’t have a clue how to balance a check book or to begin writing a term paper any sooner than the night before it was due. All true.

But thanks to my cousin, Kathy, I learned to bake a pie while I was in college. I’m putting that down as my #1 achievement, sad as that may sound to those of you who made Dean’s List. I’ll own it.

As kids, Kathy and I grew up a few miles from each other on Long Island. We shared family meals and holidays. We spent shimmery afternoons playing hide-and-seek in the apple orchard across from her house. Now, by coincidence, we had both relocated to Cortland. I was a student (at least some of the time), and she was a young wife and mother.

I’ll blame this on her, but it surely could have been my fault: Somehow, we got hooked on General Hospital. Since I didn’t own a TV, I would stop by her apartment a few afternoons a week to see what was happening in Port Charles. She would put her son down for his nap. After the scintillating dialogue and plot twists had consumed an hour, we’d tiptoe past her sleeping toddler’s room and go to the kitchen.

She would make a pie. I was her helper, doing the easy jobs, like whisking the flour and sugar together or coaxing ice water from cubes. Kathy would use her pastry blender to cut in the shortening. Then her fingers — quick and deliberate — to form tiny pebbles of dough before she would begin drizzling in the water.

Kathy came from a home where my aunt made everything from scratch, even brioche French toast. My mother was most comfortable reaching for an easy fix in the freezer and had a whole comedy routine about it. She called herself “The Swanson family’s best friend.”

Kathy was also the cute one — blonde and perky, and a cheerleader. I was the spindly one who took forever to grow into her stork legs. Then, in our late teens, it all changed. She married young and had a baby. I went off to college. As I was making fraternity parties and football games my full-time endeavor, Kathy was planning casseroles on a budget and researching preschools.

“I think I’m going to break up with Paul,” I might say as we baked on those lazy afternoons. She would already be crimping the dough into the pie pan as I was still going through the merits (or shortcomings) of Paul, or Tim, or Peter. She kept them all straight, a credit to her cousin love.

She talked about toilet training, and I tried to add comments where I could. We told stories about our mothers. We worried General Hospital was turning our brains to mush, but admitted we couldn’t give it up. We’d chat up until the last minute, until her son began calling, “Mama!” from his crib or her husband came through the door after a day of classes.

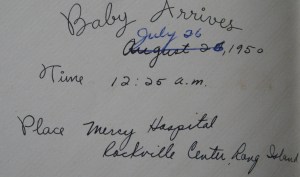

A few weeks before graduation, I wrote out the recipe. I thought I’d need the exact amounts if I wanted to recreate Kathy’s pies.

I can see the card has been used often in the years since I left Kathy and left Cortland even though pies aren’t hard to make. Only five ingredients, six if you count the ice water.

But even talented cooks might read the recipe for Kathy’s crust and fall short. Because it’s all in the wrist and the fingers. Best made when you’re laughing, or sharing a childhood secret. And letting a slow, delicious afternoon wash over you. And never forgetting it.